Recent Developments in Online Contracts and Liability Waivers

Two recent cases—one in the Seventh Circuit and one in the Wisconsin Supreme Court—struck down broad contracts seeking to bind consumers who had no opportunity to negotiate terms. While the cases deal with completely different subject matter and apply different substantive law, both reached similar results. Companies and customers alike should pay heed.

* * *

Clickwrap agreements are agreements formed on the Internet. Like all contracts, a clickwrap agreement requires that both parties mutually assent or agree to the terms of the contract. Many website providers seek users’ agreement by requiring the user to click a button or check a box bearing the words “I Agree” after posting terms and conditions adjacent to or below the click-button or check-box. In other words, the website requires the user to engage in some affirmative conduct acknowledging the terms of the online contract.

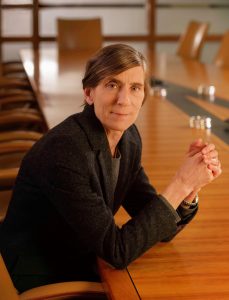

The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals in Sgouros v. TransUnion Corp., No. 15-1371 (7th Cir. March 25, 2016) (applying Illinois law), reminds website providers that not all clicks or checks are sufficient to indicate that the user agreed to online terms of service. The court declined to enforce an arbitration provision because the provision was not immediately visible in the scrollable window, and the site did not require the user to scroll to the bottom of the window or to first click on the scroll box. Nor did the site contain a clearly labeled hyperlink to the agreement next to an “I Agree” button. Chief Judge Diane Wood (who is frequently mentioned in conjunction with vacancies on the U.S. Supreme Court) wrote for the court in an opinion that gives website providers a clear indication of what is needed to make an online contract binding. Click here for a copy of the decision which contains screenshots from the website.

The plaintiff consumer had purchased a credit score from TransUnion’s website. To finalize the transaction, the plaintiff had to complete three different steps or screens on the website. The webpage for “Step 2” asked him for an account username and password and for his credit card information, including home and user billing addresses. Below these fields was a rectangular scrollable window in which only the first two-and-a-half lines of a ten-page “Service Agreement” were visible. In order to view the full agreement (and the mandatory arbitration provision on page 8), a user could scroll down the box to access the full text of the agreement. However, the hyperlinked version was labeled only “Printable Version”–not “Terms of Use” or “Service Agreement.” Immediately under the scroll box was a hyperlink to a printable version of the agreement and a bold-faced disclosure that by clicking the button, the user was authorizing TransUnion to obtain credit information. Below this disclosure was a button with the words “I accept and continue to step 3.”

The Seventh Circuit held that the layout and language of the website did not provide the plaintiff with reasonable notice that the purchase of a credit score was subject to the agreement. The court faulted TransUnion for actively misleading the plaintiff. The bold text below the scroll window told the user that clicking on the box constituted his authorization for TransUnion to obtain his personal information. It said nothing about contractual terms. The text distracted the user from the service agreement by informing him that clicking served a purpose unrelated to the agreement.

What would have been reasonable notice? Chief Judge Wood noted that “a website might be able to bind users to a service agreement by placing the agreement, or a scroll box containing the agreement, or a clearly labeled hyperlink to the agreement, next to an ‘I Accept’ button that unambiguously pertains to that agreement.” Slip op. at 13. Judge Wood noted that there are undoubtedly other ways to accomplish the goal of reasonable notice of assent to an online agreement. The scrollable window is not, in itself, sufficient for the creation of a binding contract.

* * *

While Sgouros involved an application of Illinois law, the Wisconsin Supreme Court also recently held that Wisconsin law is also skeptical of broad contracts that consumers have no ability to negotiate. In Roberts v. T.H.E. Ins. Co., 2016 WI 20 (Mar. 30, 2016), the Wisconsin Supreme Court, in a 5-2 decision, held that a hot air balloon company that donated free hot air balloon rides during a charity event could be sued by a plaintiff who suffered injuries when one of the tethers holding the balloon broke.

The plaintiff attended a charity event sponsored by one private organization at a shooting range owned by another private organization. Sundog Ballooning LLC donated free tethered hot air balloon rides at the event. The balloon was tethered to two trees and a pick-up truck. The plaintiff signed a waiver of liability and stood in line for a ride. Strong winds caused one of the balloon’s tether lines to snap. As a result, the untethered balloon moved toward the spectators in line. The plaintiff was injured when she was struck by the balloon’s basket. In the subsequent lawsuit, Sundog argued that the plaintiff’s negligence claims were barred because it had recreational immunity under Wis. Stat. § 895.52, which gives property owners immunity when others use their property for recreation, and because the plaintiff signed a liability waiver. The Circuit Court granted summary judgment to Sundog, concluding that Sundog was immune under the statute, and the Court of Appeals affirmed. See id., ¶¶ 14, 16.

The Supreme Court reversed. The Court held that the recreational immunity statute did not protect the balloon company in this instance. See id., ¶ 46. (Justice Rebecca Bradley wrote a dissent, id., ¶¶ 132-49, her first authored opinion since Governor Walker appointed her to the Supreme Court last October.) The Court also held that the company’s liability waiver form was unenforceable. See id., ¶ 63.

The Supreme Court explained that, because the liability waiver the balloon company required plaintiff to sign violated public policy, it could not foreclose plaintiff’s negligence claim. The Court, after summarizing prior case law, noted that the waiver was “overly broad and all-inclusive,” id., ¶ 59, and that it was unclear as to whether injuries sustained while waiting in line for the ride—which is what the plaintiff was doing when she was struck by the balloon basket—were within the plaintiff’s understanding of what was covered by the waiver, see id., ¶ 60. The Court also found the waiver deficient because it was a form contract that provided no opportunity for the plaintiff or other riders to bargain or negotiate over the exculpatory language. See id., ¶¶ 61-62.

* * *

The Sgouros and Roberts decisions come from two separate courts, apply two different states’ substantive law, and present two very different factual scenarios. Yet these two decisions, issued only days apart, make clear that courts continue to cast a wary eye upon efforts by companies to enforce contracts of adhesion on consumers who had no opportunity to negotiation the terms and may not even have been aware of what the terms provided.